Similar to James, I also plan on going into the

medical field. Much of what I have to

say is similar, as our two fields coincide, but I will attempt to make my post

as unique as I can, or at least give it a different flavor through my own

voice.

I am still ambivalent and oscillating as to what

exact study I am going to devote my career to, but I have narrowed the choices

down mainly to pharmacy and surgery (and also maybe neurology). Though the realms are quite different in

terms of prescribing and physically applying learned medical skills, the

rhetoric employed is nearly identical.

|

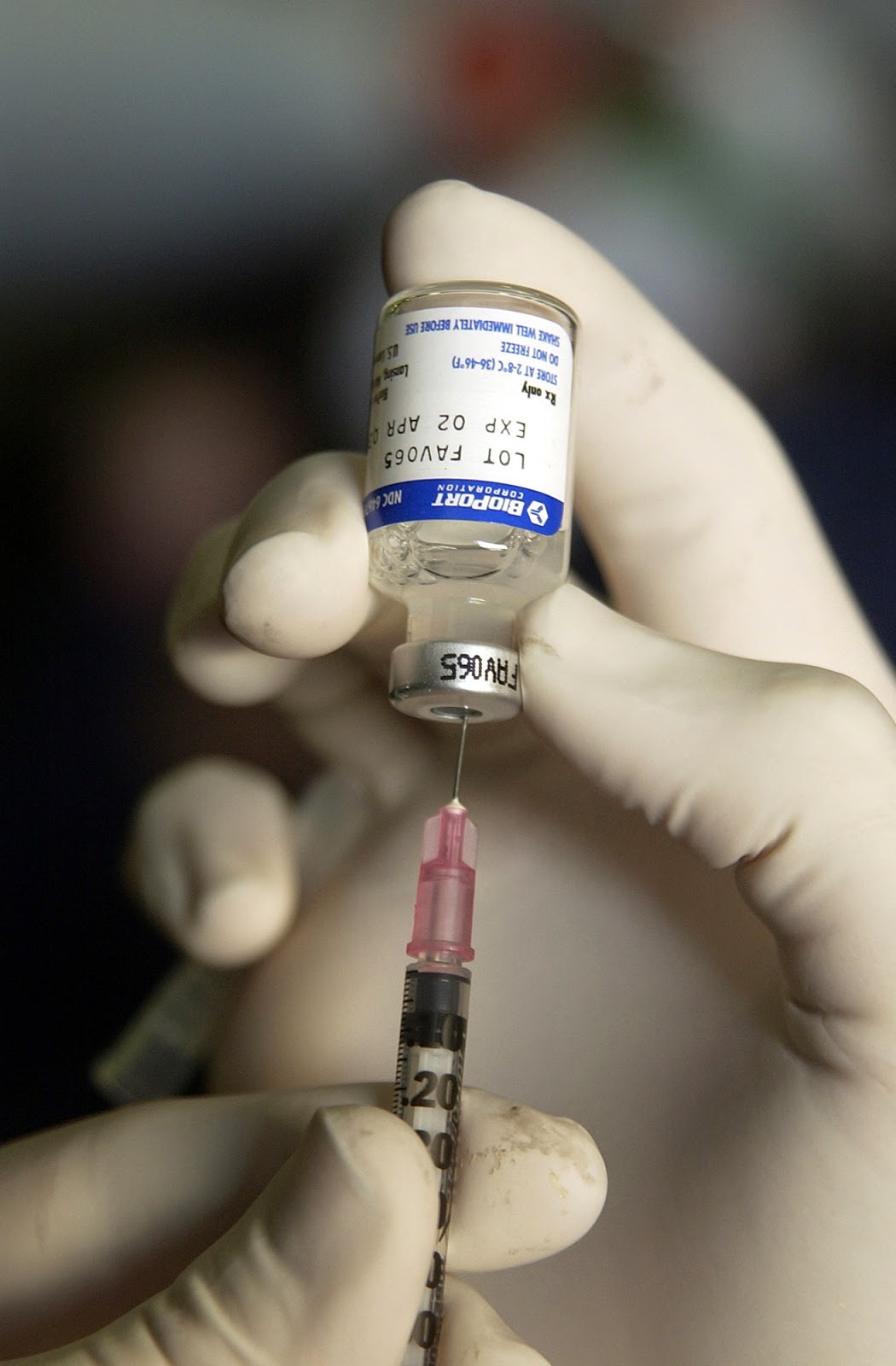

| One must know what to put in the syringe, and where best to put the syringe, while also convincing the patient to accept the syringe. |

As a physician or surgeon, communication first takes

place in the office or in the operation room, depending on the patient's

current circumstances being dire, or slightly less so. Either way, be it an emergency or a routine

checkup, the patient must be convinced via oral or written reasoning and information

as to whether or not to go through with what the doctor professes is

"best." This can be an easy

process at times, as the authoritative presence of someone who has spent a

large portion of their life to study and practice bears much weight. Conversely, a stubborn or skeptical patient

might require substantial counseling before accepting or rejecting aid. The outcome of this decision is in part

determined by urgency and the gravity of the patient's condition, but much of

the time is also heavily reliant on how effective the doctor is in

persuasion.

"To take this medicine or that medicine—or no

medicine," or "to go under the knife and radiation, or risk it"

are some of the dilemmas patients must acquire an opinion on. "Is it worth it," and "what is 'it?'" Before making a decision to heed or dismiss

the advice of the doctor, the patient must better understand the nature of

their own condition, a worrisome need readily assuaged by said physician or

surgeon.

|

| Take the right one and you live, but take the wrong one and you die. Better ask the doctor first. |

In theory, the doctor is the more knowledgeable of

the two with regards to the patient, no doubt due to numerous years of learning

and practice before actual application even begins, but this is not always the

case. In general, yes, the patient feels

a sense of inferiority to the doctor, or possibly just respect for the medical

position, but this does often lead to excessive pride in the doctor. This "God Complex," as James put

it, is a force that must be monitored.

In my own personal experience, I had a medical

tragedy that kept me out of school for two years (and continues to inhibit my

success in academics even now). Fearing

for my health and even my life, I consulted a doctor for their professional

diagnosis. Going into the meeting, I had

a theory as to what had happened to me, but the doctor disregarded the thought

and labeled it "impossible." Putting

me through all the motions for the tests that he thought I needed to go through, the results concluded that

nothing was wrong with me—a self-fulfilling prophecy that deeply offended

me. My proposition was to look into a

second, "impossibly" rare scenario, but I was merely stuck with a

massive painkiller shot and sent home.

|

| Though the Tenth Doctor might be experienced, I do not think that he has the appropriate "experience" for solving most medical issues, nor of harboring the corresponding ethos. |

Months later, I was still unable to properly

function, and after attempting to return to school, was forced to go back home

and seek further medical assistance.

Something was wrong with me,

and after meeting with another, more receptive doctor, we found that I indeed

had suffered the exact condition that I had suspected and feared.

To make a long story short, a doctor must make

excellent use of logos in assessing issues in a patient and providing a train

of thought leading said patient to accepting help. This is not all, however, because though the

doctor must exercise skillful epideictic oratory (and even judicial oratory to

demonstrate prior experiences and results), they must do it in a way so as not

to dissuade the patient from

accepting the physician's or surgeon's ethos.

Additionally, in order to be the most effective doctor, one must be

willing to listen to the plea of the patient, as neither of the two parties are

operating or prescribing for themselves.

Without a proper connection of minds under mutual respect, a doctor's

rhetoric can still fail him or her. Looking

back at my own interest in this field and my unfortunate, but eye-opening

event, I wish to pursue the path of biology with a wiser gait.

You make many good points, especially regarding the necessity of mutual respect. Rhetoric takes an unselfish turn when the doctor must employ it to truly serve and help the patient, rather than achieve his or her purposes.

ReplyDeleteMy mom has worked among doctors for over 20 years, she always says that the best doctors are compassionate and caring people. She has often said that there need to be more doctors who really care, not to the point where the professional patient-physician relationship is breached or the doctor becomes too attached, but to the point where the patient can actually trust and really heal. I think that's probably something that you were able to see with your health struggles that you shared.

ReplyDeleteGreat insights Thomas.

ReplyDeleteI think its extremely difficult to persuade someone if they have already made up their mind about something. I think this shows the two sides of rhetoric that the ancient greeks and romans both feared and respected. If used correctly, rhetoric can be a force for much good and progress, if used incorrectly it can give way to selfish and prideful ends.

I wish you the best of luck as you face your medical condition.

Thank you for your thoughts.

Delete