|

| What a mustache. |

Leon Trotsky's real name was Lev Davidovich Bronstein, but the lack of consistency in his identity didn't seem to affect his ability to stick to the truth when he predicted the future. Trotsky's The Proletariat and the Revolution is an outline for the working class to use as they rise up against the government. Political riots had broken out in 1903-4 as a result of dissatisfaction with the government (with the failed Russo-Japanese War and other general stupidness), but the working class had abandoned their revolutionary cause. So Trotsky came in to revive the efforts.

To map out the proletarian revolution, Trotsky uses a great deal of anthypophora (i.e. asking questions and then answering them himself). This format is an appeal to logos, even if it isn't as sound as a syllogism or some statistical proof. It is clear. It is concise. It is simplified. "How do we do this? Why, we do this." Very appealing.

This clear-concise-simplified-ness is backed up by pleasant pockets of lists and repetitions. Trotsky uses a great deal of "we ought"'s as nails to hammer in his message. It's an indirect way of commanding that builds Trotsky's ethos ("Hey, I've thought this through. I have enough authority to say we should do this.). It also smothers his argument in a heap of oughts, each one richer and more convincing than the one previous.

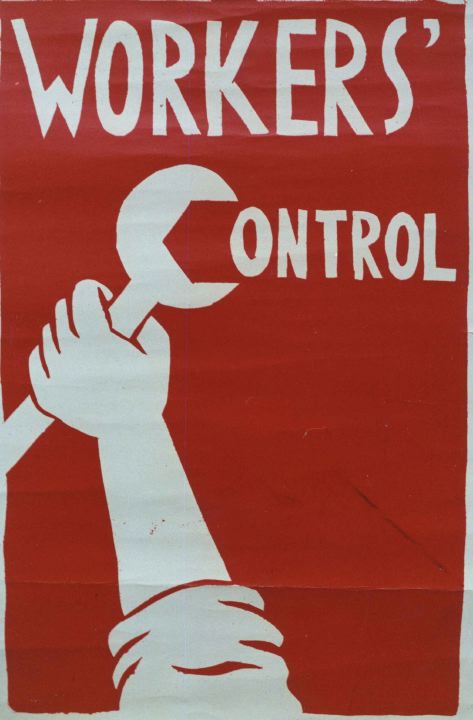

|

| That's what I do with my wrenches. |

AND THE CROWD GOES WILD!

Trotsky's words aren't the most pathos-sparking, but his direct, low-style speech is incredibly attractive to the logic. The proletariat must have taken his words to heart, too, because the revolution turned out almost exactly like his roadmap. I guess all a revolution needs is an outline to run with--and then the runners to run with it.

Pity taken.

ReplyDeleteIt is interesting how Leon Trotsky asks questions and then answers them himself. By answering his own questions, it does not give the listener anytime to think of an answer to the question themselves and so the speaker is subjecting the listener to his reasoning, because the listener only has time to agree before he moves on. So I can see why he got a lot of people to "be runners to run with it."

How do you think his audience affected the way his message was received? I think most often audiences are driven by emotion than logic. You mentioned that his suggestions were followed almost like a roadmap, why do you think the proletariat "took his words to heart?"

ReplyDeleteGood question. I guess it appealed to their pathos through logic. Like Dr. Burton was saying, the appeals are so intertwined. Such a logical argument also appeals to our sense of confidence and courage. Planting the seed of the easiness of the way in the minds of the people (through logic) can really increase their motivation.

ReplyDelete