I was

thirteen years old, and I did not want

to take a Spanish class.

The whole world was already taking

Spanish, and besides, my older sister had taken French and loved it. So despite

my parents’ warnings that Spanish would be more useful, I enrolled in French I

for my eighth grade year. French I led to French II, which led (eventually) to

French 322. In the middle of that great journey, I came across a thought: what

about French teaching?

So I looked into it and discovered

that which already begs for attention: in order to teach French, you have to know French…and really know French. It would be a little tough to teach a language

when you’ve never been immersed in it before, wouldn’t it?

So I looked into it and discovered

that which already begs for attention: in order to teach French, you have to know French…and really know French. It would be a little tough to teach a language

when you’ve never been immersed in it before, wouldn’t it?

Underneath that fact, though, there

is more to being a French teacher. It’s not just about saying your “bonjour”’s and your “oui oui”’s. It’s about knowing how to communicate

with certain audiences, as well as how to use knowledge of French teaching history,

in a way that benefits students the most.

Ruminations on Communications

There is a problem in junior high

and high schools in the United States (among others): the lack of funding for

humanities subjects like French. In order to keep funding for your subject, you

must be able to convince a variety of audiences that the French language

matters in education. Considering each of these audiences’ values before

presenting your arguments can help you keep your subject in schools.

The Head Honchos

One audience you’ll encounter is the

school administrators. Because they are the ones who will be cutting the

funding for French classes, or at least delivering the bad news, you’ll need to

stuff some good stuff up your sleeve to convince them that French is needed in

schools.

One audience you’ll encounter is the

school administrators. Because they are the ones who will be cutting the

funding for French classes, or at least delivering the bad news, you’ll need to

stuff some good stuff up your sleeve to convince them that French is needed in

schools.

Administrators are academics, right? They thus

value professionalism, statistics, and good solid reasoning. Appealing to these

values requires a confident appearance coupled with your best pressed slacks or

that black pencil skirt. This shows that you are serious about your topic, and

that you understand the hierarchy of school positions. You also have to do some

genuine research beforehand—find a couple studies with graphs to display, for

example. Do a brief study yourself at your school if you can (making sure, of

course, that all of this research points to how French language learning

benefits students). Then, show them that you know what you’re talking about.

Make straightforward points that represent a clear pathway of logic. Create multiple

syllogisms, emphasizing the conclusions about—or the advantages of—French as a

part in the whole of education.

The Young Whipper-Snappers

Of course, your most frequent audience

will be students. Convincing these little buggers that French is a worthy

pursuit (which will lead to larger class sizes and thus more funding) is a

different task altogether.

Students value entertainment,

familiarity of tone, and application to real life. For your case to be

convincing, all of these elements must be included. So say you’re doing a

beginning-of-the-year presentation to students about how French can be of use

to them in their education. Make it an online presentation, like a PowerPoint

or a Prezi. Start it with a video (a

funny one that students might already know would be best). Keep the slides

interesting throughout the presentation with music and pictures that keep their

attention. Now that you’ve got them with the technology, make sure that your tone

doesn’t betray your status. Just because you’re going to be their French

professor doesn’t mean that you’re better than them—so make sure your voice

isn’t sending that message. Throw in some hip teenager lingo, for instance,

along with some funny French words. Get on their level. Show that you care not

just about their presence in your class, but about their general educational well

being. That can definitely boost your points with the kiddos. But some of them

might then get to the point where they start wondering, How does this matter in real life? One of the things that first caught

my attention about French was how it would connect me to other people and other

parts of the world that I had never studied or seen before. Using this little

tidbit could help attract some of those students who haven’t thought about

French before but have a deep sense of curiosity or wanderlust.

Students value entertainment,

familiarity of tone, and application to real life. For your case to be

convincing, all of these elements must be included. So say you’re doing a

beginning-of-the-year presentation to students about how French can be of use

to them in their education. Make it an online presentation, like a PowerPoint

or a Prezi. Start it with a video (a

funny one that students might already know would be best). Keep the slides

interesting throughout the presentation with music and pictures that keep their

attention. Now that you’ve got them with the technology, make sure that your tone

doesn’t betray your status. Just because you’re going to be their French

professor doesn’t mean that you’re better than them—so make sure your voice

isn’t sending that message. Throw in some hip teenager lingo, for instance,

along with some funny French words. Get on their level. Show that you care not

just about their presence in your class, but about their general educational well

being. That can definitely boost your points with the kiddos. But some of them

might then get to the point where they start wondering, How does this matter in real life? One of the things that first caught

my attention about French was how it would connect me to other people and other

parts of the world that I had never studied or seen before. Using this little

tidbit could help attract some of those students who haven’t thought about

French before but have a deep sense of curiosity or wanderlust.

The Tale of French Teaching

Before the Renaissance, French teaching

emphasized conversation more than anything. Students learned as if from traveler’s

bilingual dictionaries—how to talk about the pantalons they put on that morning, how to describe the nourriture they ate for lunch, how to

ask for directions to the cinéma. Their textbooks were “elementary

grammars…and treatises” that addressed little more than “the occupations of

daily life” (Simoni). Grammar was left on the sidelines. Teachers—who were

often emigrants—did little more than move their students to conversational

ability. Granted, at that time, French

teaching wasn’t exactly standardized.

Before the Renaissance, French teaching

emphasized conversation more than anything. Students learned as if from traveler’s

bilingual dictionaries—how to talk about the pantalons they put on that morning, how to describe the nourriture they ate for lunch, how to

ask for directions to the cinéma. Their textbooks were “elementary

grammars…and treatises” that addressed little more than “the occupations of

daily life” (Simoni). Grammar was left on the sidelines. Teachers—who were

often emigrants—did little more than move their students to conversational

ability. Granted, at that time, French

teaching wasn’t exactly standardized.

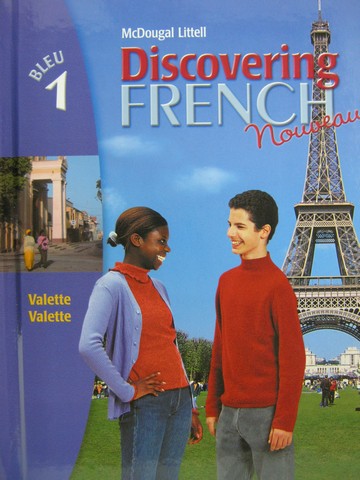

French teaching in modern history, up to the present, is much the opposite. The student’s first encounter with French often consists of just standardized learning of grammar and vocabulary (using textbooks that may or may not be from the ‘80’s). These “‘pre-communicative’ knowledge and skills” (Littlewood) are essential foundations, but they don’t get students to the communicative part of language. And it’s the communicative part that really makes knowledge of language useful and meaningful.

So, what? Can this historical

context make a difference in how French teachers make a difference in students’

lives? Indeed, it can. Knowledge about the history of French teaching can help

create the ideal learning environment for students. The approach is to balance the

distant and recent past.

It can be difficult for beginning

students especially to have the courage to communicate in a secondary language

in class. To embolden the shier ones requires, quite simply, frequent and effective

conversation activities. Integrate simple and useful French phrases into the

curriculum so that students can speak in the classroom while they are learning other grammar and vocabulary rules, not apart from that learning. French

teachers should also speak in French at least during part of class, working up

to entire class times in French within the first couple years of language

courses.

French teaching is more than being

fluent in French. In order to persuade students and administrators to recognize

the value of French classes, you must possess rhetorical and historical knowledge.

Such tools can and will have an incredible impact on how much attention and funding

your language program receives, as well as how you’re

your students learn and end up being able to utilize their language skills.

Works Cited

Littlewood, William

T. "Form and Meaning in Language-Teaching Methodology." The

Modern Language Journal (1980): 441. EBSCO. Web. 3 Dec. 2014.

Simonini, R. C.

"The Genesis of Modern Foreign Language Teaching." The

Modern

Language Journal (1951): 185-86. EBSCO. Web. 3

Dec. 2014.

No comments:

Post a Comment